I’ve talked about this in various venues and also cover it in my Pluralsight REST Fundamentals course, but the topic of how to version RESTful services has been popping up a bunch recently on some of the ASP.NET Web API discussion lists, and my friend Daniel Roth asked if I could serialize some of that presentation content into a blog post – so here goes.

First, note that while the focus here is on RESTful services and not just HTTP services, the same principles can potentially apply to HTTP services that are not fully RESTful (for example, HTTP services that do not use hypermedia as a state transition mechanism).

When talking about versioning, the most important question to ask is “what are you wanting to version?” The logical extension to this question is, “what is the contract between your service and client?” This is naturally important since the contract is the thing you want to version.

In the “old world” of Web services, the contract was the service. Service actions (and associated semantics) along with data formats and other metadata were covered by the definition of the service, which was exposed as a single URL (the service, that is – I’m grouping together all RMM L0 services here). As such, when it came to the question of how to version the service, the answer was generally pretty simple: if the contract is the service, and the service is exposed as a URL, then the solution is to version the URL. As such, you’ll see a lot of this if you browse around –

(Not trying to pick on NuGet here – it just happens to be a service API that I’m pretty familiar with at the moment)

It doesn’t take much imagination to see how unwieldy this can get after even a few iterations – especially when you’re clients are interacting with the service by generating strongly typed proxies and then pretending that there is no network (yes, I am picking on WCF here).

So how is this different for RESTful services?

Well, we should start by again asking the question, “What is the contract for a RESTful service?” The answer is, IMHO, the uniform interface. The uniform interface is made up of 4 constraints –

- Identification of resources

- Manipulation through representations

- Self-descriptive messages

- Hypermedia as the engine of application state (HATEOAS)

While all of these constraints are important to understand and take into consideration for the overall design of a RESTful system, I’m going to highlight the first 2 with respect to versioning.

First, let’s look at resources. A resource is any named information or concept – this is nice from a philosophical perspective, but maybe a little less helpful in how it enables us to think about versioning, so let’s look at it another way (as Fielding describes). A resource is a 0..n mapping between an identifier and a set of entities that changes over time. Here’s a concrete example:

I have 3 daughters: Grace, Sarah, and Abigail. However, this was not always the case – in fact, during the time period before Grace was born, the resource map of my family looked like the following:

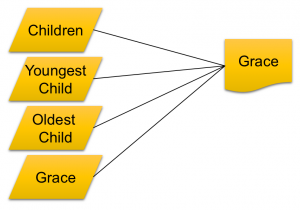

As you can see, I had defined (in my mind) a bunch of named concepts – and at that point in time, they didn’t map to any actual entities (e.g. kids). Now, when Grace was born, the resource map looked like the following:

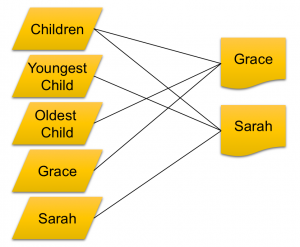

As you can see here, all of my named concepts map to a single entity – Grace. But what about when Sarah came along? Then the map changed to the following:

As you can now see, my “children” collection resource maps to multiple entities, and “youngest child” now maps to Sarah rather than Grace.

The point here is that the resource concept has not changed here – and more importantly, though the specific entity mappings have changed over time, the service has done this in a way that preserves the meaning of identified domain abstraction (e.g. children).

A representation, on the other hand, is an opaque string of bytes that is effectively a manifestation of a resource. Representations can come in many different formats and the process of selecting the best format for a given client-server interaction is called content negotiation. The self-descriptive message constraint of the uniform interface adds that the information needed to process a representation, regardless of format, is passed in the message itself.

I wanted to give this brief explanation of resources and representations because it’s important to have a clear understanding of what they are so that you can know when to version them. So let’s get back to versioning…

So, if the contract for a RESTful service is the uniform interface, then the answer to the question of how to version the service is “it depends on which constraint of the uniform interface you’re changing.” In my experience, there are 3 common ways that you can version (I’m sure there are more, but these are the 3 that I’ve come across most regularly).

Versioning Strategy 1: Adding content to a representation

In the case where you’re adding something to a representation – let’s say that you’re adding a new data field “SpendingLimit” to a customer state block as follows:

{

"Name": "Some Customer",

...

"SpendingLimit":"unbounded"

}

In this case, the answer to the versioning question is to just add it. Now, this assumes that your clients will ignore what they don’t understand. If you’ve written clients in such a way that you can’t make that assumption, then you should fix your clients – or perhaps you need to look at the next strategy.

Versioning Strategy 2: Breaking changes in a representation

In the case where you’re either removing or renaming content from an existing representation design, you will be breaking clients. This is because even if they are built to ignore what they don’t understand, by making this sort of change on the server, you’re changing what they already understand. In this case, you want to look at versioning your representation. HTTP provides a great facility for doing this using content negotiation. For example, consider the following:

GET http://localhost:8800/bugs HTTP/1.1

User-Agent: Fiddler

Host: localhost:8800

accept: text/vnd.howard.bugs.v1+html

This request gives me the following response fragment – as you can see, I’m working from an HTML base media type:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Length: 1107

Content-Type: text/vnd.howard.bugs.v1+html

...

<div id="links">

<h2>Navigation</h2>

<a href="/bugs" rel="index">Index</a><br/>

<a href="/bugs/backlog" rel="backlog">Backlog</a><br/>

<a href="/bugs/working" rel="working">Working</a><br/>

<a href="/bugs/qa" rel="qa">In QA</a><br/>

<a href="/bugs/done" rel="done">Done</a>

</div>

Now what if, for some reason, I needed to change the link relationship values? Remember that based on the hypermedia constraint of the uniform interface, my client needs to understand (e.g. have logic written against) those link relationship values, so renaming them would break existing clients. However, in this case, I’m not really changing the meaning of the resources or the entities that the resources map to. Therefore, I can version my representation and enable clients that know how to work with the newer version to request the newer version using the HTTP accept header as follows:

Therefore, this request:

GET http://localhost:8800/bugs HTTP/1.1

User-Agent: Fiddler

Host: localhost:8800

accept: text/vnd.howard.bugs.v2+html

Will now give me the new response format:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Length: 1107

Content-Type: text/vnd.howard.bugs.v2+html

...

<div id="links">

<h2>Navigation</h2>

<a href="/bugs" rel="index">Index</a><br/>

<a href="/bugs/backlog" rel="backlog">Backlog</a><br/>

<a href="/bugs/working" rel="active">Active</a><br/>

<a href="/bugs/qa" rel="testing">Testing</a><br/>

<a href="/bugs/done" rel="closed">Closed</a>

</div>

One other thing that I want to mention here – you’ve probably noticed that I’m using the language of representation design and representation versioning as opposed to content type design/versioning. This is deliberate in that many (most?) times, you’re going to design your representations completely on top of existing content types (e.g. xml/json/html/hal/etc). Without wading into the custom media type debate in this post, my point is that when I’m talking about versioning the representation here, I’m talking about versioning the domain-specific aspects of your representation that your client needs to be aware of.

Versioning a representation over an existing media type will look slightly differently from what’s shown above in that you’ll pass a standard media type identifier in the HTTP accept header along with an additional metadata element to identify your representation-specific aspects and then do content negotiation based on the combined description. There are several different ways to add the representation-specific metadata, including media type parameters and custom HTTP headers.

Versioning Strategy 3: Breaking the semantic map

In both of the prior strategies, all changes, breaking and non-breaking, have been related to the representations. This is a really good thing as it enables the resources (and more importantly, the URL resource identifiers) to remain stable over time. However, there may be occasions – hopefully rarely – when you need to break the meaning of a resource and therefore the mapping between the resource and its set of entities. As an example, as I get older and my kids grow up and leave, let’s say that I start returning my pets as children. In this case, I’ve changed the meaning of the “children” resource and thereby broken that aspect of the contract between my client and service. The solution then, in this case, is to version the resource identifier itself.

If I did a lot of this sort of resource versioning, it is very possible that I could end up with an ugly-looking URL space. But REST was never about pretty URLs and the whole point of the hypermedia constraint is that clients should not need to know how to construct those URLs in the first place – so it really doesn’t matter whether they’re pretty or ugly – to your client, they’re just strings.

So to summarize

This post ended up being longer than I had planned, so here’s the summary.

- In REST, the contract between clients and services is the uniform interface

- How you version depends on what part of the uniform interface you’re changing

- If you’re adding only, go ahead and just add it to the representation. Your clients should ignore what they don’t understand

- If you’re making a breaking change to the representation, version the representation and use content negotiation to serve the right representation version to clients

- If you’re changing the meaning of the resource by changing the types of entities it maps to, version the resource identifier (e.g. URL)