As large technology companies transition to services and APIs, there will inevitably be quite a bit of debate around what data a service “owns” (and related: how to stop another service from owning that data), what document schemas should be supported, how to create and expose Swagger documents, and so on. As I’ve observed and participated in many of these kinds of discussions, I am convinced that while none of these discussions are fundamentally bad, they are all secondary to a well thought-out data model based on a directed graph. Put another way, with a cohesive data model, otherwise contentious (and therefore political) debates around the number, purpose, and ownership of services, become data-driven conversations about naturally-emerging clusters of terms in a graph that describes the company’s data.

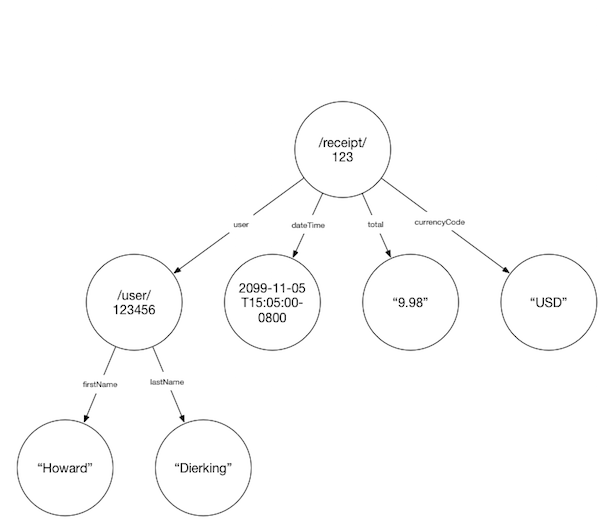

From the data ownership perspective, a graph-based approach changes the conversation from one of service ownership to one of naming. An example may help here. Consider the fact that a receipt contains a reference to a user. From the view of service design, receipt and image data have a network boundary between them as they are managed by two different services.

###### http://api.concursolutions.com/receipt/123 ######

{

"user": "http://api.concursolutions.com/user/123456",

"dateTime": "2099-11-05T15:05:00-0800",

"total": "9.98",

"currencyCode": "USD"

}

###### http://api.concursolutions.com/user/123456 ######

{

"firstName": "Howard",

"lastName": "Dierking"

}

Logically, these 2 resources are a part of the same graph. However, the vanilla JSON approach doesn’t give us the tools to really interact with the data this way.

What if, for example, we want to optimize performance by folding these 2 resources into the receipt resource, as follows?

{

"user": {

"self": "http://api.concursolutions.com/user/123456",

"firstName": "Howard",

"lastName": "Dierking"

},

"dateTime": "2099-11-05T15:05:00-0800",

"total": "9.98",

"currencyCode": "USD"

}

In this traditional approach, this would be fraught with problems. One relatively pedestrian problem is that “user” needs to now have an object as its value and we need to find another key name for the URL. A bigger problem, however, is that firstName and lastName have no meaning outside of the document in which they’re defined, which in this case is the receipt document http://api.concursolutions.com/receipt/123. So by just looking at the document, a machine has no real way of knowing that these properties are describing something other than the receipt. You only know that these properties are describing a user because you can look at the containing object, see that it’s called “user”, and then infer that firstName and lastName are describing that user. Put another way, you can draw these conclusions because you’re a human - and humans rock.

To solve this problem, there’s really just one thing that we need to do - and that’s to namespace all of the keys. XML actually had XML namespaces for that sort of thing and in JSON we use fully qualified URLs via JSON-LD. With just a few small changes, I can get a completely unambiguous, composite document.

{

"@context":{

"@vocab": "http://schema.concursolutions.com/receipts#",

"u": "http://schema.concursolutions.com/user#"

},

"@id": "http://api.concursolutions.com/receipt/123",

"user": {

"@id": "http://api.concursolutions.com/user/123456",

"u:firstName": "Howard",

"u:lastName": "Dierking"

},

"dateTime": "2099-11-05T15:05:00-0800",

"total": "9.98",

"currencyCode": "USD"

}

There are really just 2 tweaks here. The first is that I added a @context object. This object sets a base namespace for receipt terms. It also adds a namespace prefix for user terms, which you can see used in the definition of firstName and lastName. When this JSON-LD document is viewed in its expanded form (which means harder for humans to read but easier for machines), you can more easily see the impact of the context.

{

"@id": "http://api.concursolutions.com/receipt/123",

"http://schema.concursolutions.com/receipts#currencyCode": "USD",

"http://schema.concursolutions.com/receipts#dateTime": "2099-11-05T15:05:00-0800",

"http://schema.concursolutions.com/receipts#total": "9.98",

"http://schema.concursolutions.com/receipts#user": {

"@id": "http://api.concursolutions.com/user/123456",

"http://schema.concursolutions.com/user#firstName": "Howard",

"http://schema.concursolutions.com/user#lastName": "Dierking"

}

}

The second thing I did was to replace the self link with JSON-LD’s @id. This is the term used by JSON-LD to say, “the value of this property should always be interpreted as a URL”. I added @ids for both user and the receipt.

Finally, because JSON-LD is compliant RDF, we can go even further and flatten this document to a graph of triples (subject, predicate, object). Representing a graph this way then makes tasks like merging graphs pretty trivial.

<http://api.concursolutions.com/receipt/123> <http://schema.concursolutions.com/receipts#currencyCode> "USD" .

<http://api.concursolutions.com/receipt/123> <http://schema.concursolutions.com/receipts#dateTime> "2099-11-05T15:05:00-0800" .

<http://api.concursolutions.com/receipt/123> <http://schema.concursolutions.com/receipts#total> "9.98" .

<http://api.concursolutions.com/receipt/123> <http://schema.concursolutions.com/receipts#user> <http://api.concursolutions.com/user/123456> .

<http://api.concursolutions.com/user/123456> <http://schema.concursolutions.com/user#firstName> "Howard" .

<http://api.concursolutions.com/user/123456> <http://schema.concursolutions.com/user#lastName> "Dierking" .