One of the less stated charters of my team is to push the bounds on system design and innovation within our company’s larger technology group. In doing so, it is expected that we will push people out of their comfort zones and while this will undoubtedly create friction, the idea is that the final outcome will be better for the larger group. While I think the final outcome is still to be determined, there are many ‘right conversations’ that are happening. One of them that I’ve been reflecting over recently is the disagreements with different central teams - especially around issues related to infrastructure and operations. Two areas where these disagreements appear to surface the most right now are related to how cloud resources should be provisioned and used, and on how our API gateway should be designed in relation to the infrastructure that hosts the services it proxies.

As I’ve been reflecting on some of these disagreements, I was struck by a thought. Most companies that came about before public cloud services existed, ours included, have developed skill for building and operating data centers. And I believe that years of this experience has formed a lens through which all infrastructure-related activities are seen - including how services are designed for the public cloud. I’m happy to be proven wrong here, but my assessment is that when it comes to public cloud services like AWS, the traditional strategy appears to be that of attempting to build a new data center on top of AWS. This is in my mind equivalent to building a “data center on a data center”, and it undermines many of the benefits of moving resources to the public cloud.

I’ll call this lens an “infrastructure first” lens, and in this post will juxtapose it with an alternate lens that I’ll call “service first”.

Comparing the Lenses

Before I get too far into this, there’s one thing I want to stress - I’m addressing the lens here, not the end result. I think it’s possible to arrive at the same design with each lens. However, I think that the service-first lens can provide some benefits over the infrastructure-first lens - specifically around agility and overall system reliability.

So let’s define terms a bit more and then draw some comparisons.

As I’m defining it, the topmost logical unit in the infrastructure-first lens is the network; within the network are data centers, and within a data center are services. Dedicated teams of network and operations engineers construct the network between and within data centers and then provision or constrain available resources within each respective data center for service teams - including “dial tone” services such as distributed key-value stores (etcd, consul.io, zookeeper), logs management, and security and compliance related capabilities. Service developers, then, optimize around their “business logic”.

By contrast, in a service-first lens, the topmost logical unit is the service, as identified by a stable name (URL). This URL and everything behind it is owned and operated by the service team. Network and operations engineering teams shift from building out a shared and constrained set of infrastructure and services to offering solutions (infrastructure, pipeline, etc.) as products to the service teams. Because service teams are ultimately accountable for the runtime characteristics of their service, they may choose to use or not use services provided by the network and operations teams.

There are some major ramifications that come out from these different lenses. Here are a few.

- In an infrastructure-first world, there are separate data center environments for different environments (e.g. dev/test/prod). In a service-first world, there are only separate names - and those names can map to whatever implementation environment that works for the service team (and that team’s customers).

- In an infrastructure-first world, a service meets the security and compliance controls of the company by way of running under centrally managed infrastructure. In a service-first world, the service team is accountable for meeting these controls and central operations teams offer centrally managed services as value-adding.

- In an infrastructure-first world, security for service-to-service communication is managed by network routes, if at all. In a service-first world, no client is trusted and authentication must be provided to every service as data.

- In an infrastructure-first world, the scale and performance characteristics of every service must necessarily be made the same as every other service because those are characteristics of the infrastructure. In a service-first world, each service implements a strategy that is germane to its requirements.

- In an infrastructure-first world, concerns like global IP ranges are important in order to enable fast communication between data centers. In a service-first world, concerns such as geographical load balancing and replication are an internal implementation detail of the service - To the outsider, there’s simply a stable URL.

A Scenario

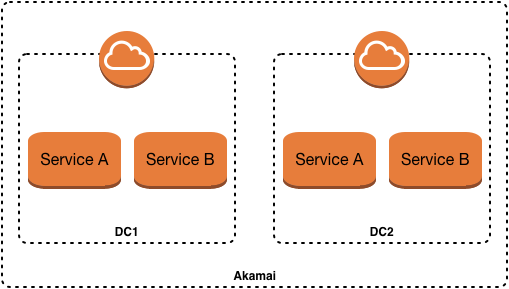

Let’s drill in for a moment on this last bullet, because it’s a scenario that I’ve heard raised on numerous occasions. Consider the following infrastructure-focused view of the world.

Though this lens, the following kinds of questions can become deeply concerning.

- ServiceA and ServiceB are both deployed into DC1 and DC2

- ServiceA (running in DC1) needs to make a request to ServiceB

- Does ServiceA call the instance of ServiceB that’s running in DC1 or DC2?

- How does ServiceA know this?

- How does the request get routed to ServiceA in DC1

- If ServiceB in DC1 is down for some reason, how can that same request from ServiceA in DC1 get routed to ServiceB in DC2?

Further (and this is where I find problems with the infrastructure-first lens), the solutions are both complex and introduce coupling between shared infrastructure and individual services. For example, in order to address the concerns above, something like the following would need to be implemented.

- Data centers would need to be carefully designed for routability to one another. This would mean, among other things, that every network interface would need to be a part of the same, non-overlapping IP address space

- Network connections would need to be made between all data centers

- Services would need to get addresses for other services from somewhere as they could not depend on stable names (again, consider the scenario where ServiceB in DC1 is down). There are a multiple ways that this problem could be solved, but the most common scenario involves using a distributed key-value store such as etcd or consul.io. For kicks sometime, do a Google search for network flapping and consul.io and see whether that’s something you want to take a big bet on just yet.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the above is pretty typical of the kinds of problems and solutions that I hear articulated by central infrastructure teams. And for quite a while, I was just scratching my head because I couldn’t understand why these were even assessed as major problems. At this point, I think that what I didn’t understand was that I was looking at the problem space through the service-first lens while they were looking at it from an infrastructure-first lens.

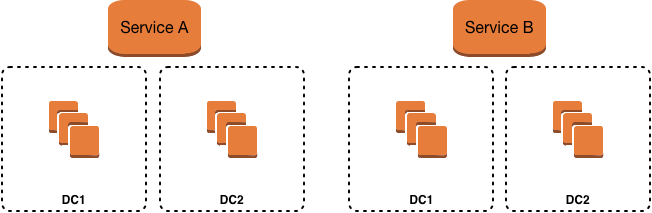

For example, consider the same logical topology viewed through the lens of service-first.

One of the key things that hopefully will jump out to you is that the physical infrastructure is conceptually not different from that of the infrastructure-first lens. The differences start becoming more apparent, however, when you look at the mechanics of how ServiceA and ServiceB communicate. Through the infrastructure-first lens, ServiceA needs to be notified in near-real-time the address of ServiceB in order to handle fail-over scenarios - and the shared infrastructure is responsible for providing that information. As a result, ServiceA is coupled to the infrastructure both functionally (it is built with an awareness of the infrastructure component that provides it with the address) and temporally (the infrastructure must be available when ServiceA makes the call to ServiceB in order to avoid cascading failures or other side-effects).

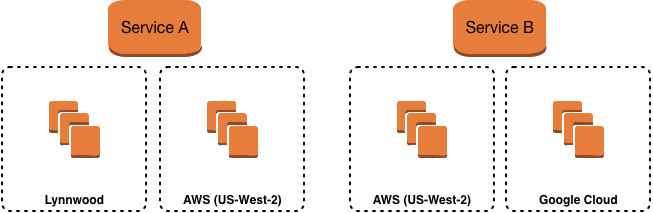

Conversely, in the service-first lens, ServiceA only knows of this named thing called ServiceB. The partitioning of infrastructure, the mechanics of fail over, etc. - all of these details are implementation details of ServiceB. From ServiceA’s perspective, ServiceB is a single thing with a stable name (URL) and that thing is either available or unavailable. Behind ServiceB’s URL, the service can be deployed in many data centers or one data center depending on its requirements. From an innovation perspective it also enables incorporating new types of infrastructure as that space evolves.

Now, as a matter of policy, it may not make sense to pursue a cross-cloud deployment strategy just yet. However, a more likely scenario is one where we acquire a company and want to be able to integrate their technology into ours without requiring a large engineering effort to shift their product onto our infrastructure. The service-first approach enables this seamlessly by simply giving those acquired services new names and then integrating at the data level.

Elevation of Infrastructure to Data

As I just alluded, the service-first lens treats constraints such as security concerns (whether runtime concerns such as authentication and authorization or internal concerns such as logging, auditing, and rapid7 scanning) as data concerns rather than infrastructure concerns. As a result, it provides flexibility both for innovation as well as cost reduction.

I will elaborate on what I mean by “elevation of concerns to be about data” by way of example. When network infrastructure cannot be relied on as a security barrier, services authenticate to one another using data-oriented techniques such as x.509 client certificates. Because the strategy is infrastructure-agnostic, it works across multiple and diverse infrastructures.

There are Trade offs

As with so many things, the devil is always in the details - and while I’ve spent a fair amount of characters trying to explain why I disagree with the infrastructure-first lens, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention what I think are some challenges with the service-first lens.

- It increases the accountability of individual service teams. This is probably the single biggest concern that comes to mind when people (myself included) think about this kind of paradigm shift as it would mean that service teams would be accountable for their entire SLA - not just their code quality as is the case today in many large enterprises. And let’s be honest - this can be more than a little intimidating. This is why I will again stress that what I’m describing is not a physical (or even logical) infrastructure topology, but rather a lens that looks first at the service and second at the infrastructure. Over time, I fully expect for there to be a convergence around infrastructure - even to the level of shared infrastructure, particularly with respect to compute clusters. In fact, I’m already seeing some really encouraging progress that’s been coming out of our DevOps team for automating the declaration, provisioning, and deploying of services to multiple classes of runtime environments. However, for there to be convergence, there must first be divergence - and in my opinion, the risk of prematurely converging on an architecture which is tied to a specific infrastructure design is greater than the risk of increasing the responsibility of individual service teams. In fact, we could also mitigate the risk of the increased scope by organizing operations and R&D groups into single, autonomous service teams.

- It gives the impression of changing the accountability of central network and operations teams. I think that I covered this in addressing the previous concern, so I won’t restate all of that here. I will add one additional point, though, in that I believe that a services-first lens would unblock teams from delivering, thereby reducing pressure on the operations team of having to have something out there to unblock teams, and allowing them to step back and focus on adding more value to service teams than what they could otherwise get from third party tools and infrastructure. On the constraints side, there are also some tools that we use for security and compliance that, because of their licensing model, still need to be maintained centrally. Again, that’s why what I’m describing here is not an implementation or architecture, but a lens.

- It can introduce some network latency. If every service is responsible for its own global infrastructure, then presumably, every call (even between services) could in theory go all the way to the network edge in order to hit the destination service’s global traffic manager. There are many, many tricks that can be put in place behind the scenes to mitigate this risk while preserving the service-first lens and some of the mechanics that emerge from it. However, there is some risk - and that risk should be kept in focus with any implementation. We should always be relentless in our measuring, and fearless in calling failure and changing course on our own ideas and implementations.

- It’s value diminishes as the number of services become larger and more fine grained. This is what’s been referred to as the nano-services antipattern and its effects are exacerbated in a service-first lens. This is because the service team is accountable for its own infrastructure. If the team is maintaining 9 servers and 1000 lines of infrastructure automation for a 100 line service, then a service-first lens may not be appropriate (though arguably, this architecture may not be appropriate in general).

In the end, the question of lens aligns with something I was recently told - that a company can scale up significantly more easily than it can scale down. Similarly, I would argue that convergence of cleanly separated (named) things is significantly simpler than trying to diverge an already-converged thing.